Net weight and gross weight are fundamental measurements in logistics, commerce, and product labeling, yet they serve distinctly different purposes. Net weight represents the weight of the product alone, excluding all packaging and containers, while gross weight represents the total weight including all packaging, protective materials, and containers. Understanding this distinction is critical for accurate shipping cost calculation, regulatory compliance, customs clearance, inventory management, and consumer transparency. The difference between these measurements directly impacts operational expenses, with gross weight determining freight charges while net weight governs product pricing and duties assessment.

Understanding the Core Definitions

Net Weight refers exclusively to the weight of the actual product itself, without any packaging, containers, or protective materials. In essence, it represents the consumable or usable portion of what is being shipped or sold. For example, when you purchase a bag of rice marked as “10 kg net weight,” those 10 kilograms represent only the rice, not the bag containing it. Net weight is determined by either weighing the product alone before packaging or by calculating it as the difference between gross weight and tare weight.

Gross Weight encompasses the total weight of the entire shipment, including the product, all packaging materials, containers, pallets, and any protective equipment. This comprehensive measurement reflects what carriers actually transport and what determines the space and handling requirements for a shipment. For a shipment of canned goods, the gross weight includes the food product, the metal can, the cardboard box, the plastic wrap, and the wooden pallet on which everything sits.

The third essential measurement is Tare Weight, which is the weight of the empty container, vehicle, or packaging materials alone, excluding the product. Understanding tare weight is crucial because it bridges net and gross weights through the fundamental relationship: Gross Weight = Net Weight + Tare Weight.

The Mathematical Relationship Between Weights

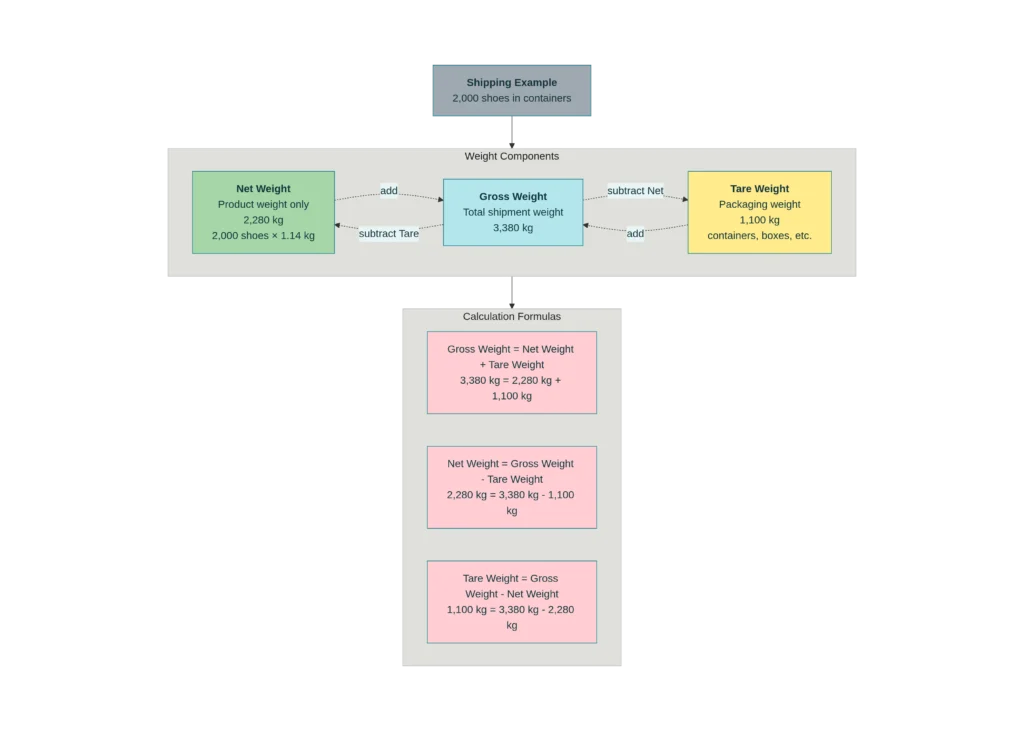

The three weight measurements maintain a precise mathematical relationship that forms the foundation of logistics calculations. The standard formulas are:

- Net Weight = Gross Weight – Tare Weight

- Gross Weight = Net Weight + Tare Weight

- Tare Weight = Gross Weight – Net Weight

A practical example illustrates these relationships clearly. Consider a shipment of 2,000 pairs of shoes from a manufacturing facility: Each shoe pair weighs 1.14 kilograms without packaging. The total net weight of the shipment is therefore 2,000 × 1.14 = 2,280 kilograms. However, each pair requires a shoebox (0.25 kg) plus smaller packaging materials. When 10 pairs are packed per carton with 200 cartons total, and a wooden pallet (600 kg) is added for stability, the total packaging weight becomes 1,100 kilograms. The gross weight calculation is therefore: 2,280 kg (net) + 1,100 kg (packaging and pallet) = 3,380 kilograms.

Key Practical Differences

The distinction between net and gross weight manifests across multiple dimensions critical to business operations:

Product Pricing and Consumer Transparency: Net weight is what consumers pay for and what manufacturers use to price their products. A food company pricing flour by weight uses net weight, ensuring customers receive the actual product quantity regardless of bag size. Regulatory bodies, including the FDA and USDA, mandate that net weight be displayed prominently on product packaging in both imperial and metric units. This requirement protects consumers and enables accurate unit price comparisons across brands.

Shipping Cost Calculations: Gross weight is the determinant for freight charges in most scenarios. Shipping companies charge based on the complete weight being transported, including all protective materials and containers, as this reflects the resources required for transportation. A logistics company quoting a shipping cost must provide the gross weight to carriers, not the net weight. For heavy or dense items, actual weight generally determines costs; for bulky but lightweight items, volumetric (dimensional) weight may supersede both, with carriers charging whichever is greater.

Customs and Import Duties: The classification of goods for customs purposes varies by jurisdiction. While some duties are assessed on net weight (the actual product being imported), other considerations factor in the total weight being shipped. Import declarations, however, typically require both measurements for clarity and compliance purposes, as customs authorities need complete information about what is crossing borders.

Transportation Safety and Compliance: Gross weight is essential for regulatory compliance because it determines whether a shipment exceeds legal weight limits for specific vehicle types and routes. A truck’s gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) must not be exceeded, and this includes all cargo and protective materials. A 20-foot shipping container has a tare weight of approximately 2,280 kilograms and can safely carry a maximum load of about 26,500 kilograms, making the maximum allowable gross weight approximately 28,780 kilograms.

Inventory and Warehouse Management: Both measurements serve different purposes in inventory systems. Net weight represents the actual inventory value and determines shelf life considerations (especially for perishables), while gross weight influences storage space allocation and material handling equipment requirements. A warehouse manager optimizing space utilization must account for the gross weight when calculating floor loading capacity and vertical stacking limits.

Industry Applications and Standards

Maritime and Container Shipping: The International Maritime Organization (IMO) requires that shippers declare the Verified Gross Mass (VGM) of containerized cargo before loading onto vessels. This declaration must include the container’s tare weight, the cargo’s net weight, and all packaging materials. A 40-foot shipping container, weighing approximately 3,780 kilograms when empty, must have its gross weight calculated and verified for safe and compliant maritime transport.

Food and Beverage Labeling: FDA regulations (21 CFR 101.105) mandate that net weight appear on the principal display panel (PDP) of food packages, positioned in the bottom 30% and in clearly legible font. The net weight statement must use both U.S. customary units (pounds and ounces) and metric units (grams or kilograms) to ensure consumer accessibility. Failure to comply with these labeling standards can result in product recalls, fines, seizures, and import refusals.

Air and Ground Freight: For air freight, which is highly sensitive to weight and space constraints, both actual (gross) weight and volumetric weight are calculated, with the higher value determining the chargeable weight. Ground freight carriers similarly use gross weight as the primary chargeable weight, though they may apply dimensional weight for extremely bulky lightweight shipments. Understanding this distinction allows shippers to optimize packaging and reduce unnecessary costs—using more compact packaging can lower volumetric weight and consequently reduce air freight charges.

Real-World Impact on Business Operations

The difference between net and gross weight directly affects profitability and operational efficiency. A manufacturer shipping 10,000 units of a product might discover that the gross weight is 30% higher than the net weight due to extensive protective packaging designed to prevent damage during transit. This 30% increase in gross weight translates directly into higher shipping costs, even though the customer only values the net weight. However, reducing packaging quality to lower gross weight risks product damage, which is significantly more costly than the shipping savings.

For e-commerce businesses, understanding these weights enables accurate shipping cost calculations to customers. Underestimating gross weight leads to undercovered costs; overestimating causes lost sales to competitors. Many successful logistics operations use weight optimization strategies—selecting packaging materials that balance protection with minimal added weight, consolidating shipments to maximize container utilization, and negotiating freight rates based on accurate gross weight data.

Import/export businesses face particular complexity because customs authorities in different countries may assess tariffs on net weight, but shipping costs are invoiced on gross weight. A shipment might incur duties based on 100 kilograms of net weight while costing freight charges on 140 kilograms of gross weight, creating a dual-cost structure that requires careful financial modeling.

Regulatory and Compliance Considerations

Accurate weight declaration is not merely operational best practice—it is a legal requirement with significant penalties for non-compliance. The NIST Handbook 133 on “Checking the Net Contents of Packaged Goods” establishes standards that manufacturers must follow. Products must contain the stated net weight with allowable tolerances depending on product type and jurisdiction; consistent underweight disclosure can trigger regulatory action.

In India, where many logistics hubs operate internationally, food manufacturers must comply with the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) labeling regulations, which mandate accurate net weight declaration. Non-compliant products face removal from shelves and potential legal consequences.

Practical Examples Across Industries

Cereal Manufacturing: A cereal box contains 500 grams of cereal (net weight). The cardboard box, plastic bag, and paper envelope together weigh 100 grams (tare weight). The gross weight is therefore 600 grams. The manufacturer prices based on 500 grams, but the retailer’s receiving department must account for the 600-gram gross weight when calculating warehouse space and freight costs.

International Footwear Shipping: An importer receiving 2,000 pairs of shoes with a net weight of 2,280 kilograms and total packaging weight of 1,100 kilograms must pay freight charges based on the 3,380-kilogram gross weight. However, customs duties are assessed on the 2,280-kilogram net weight, and inventory management tracks the 2,280 kilograms of actual merchandise value.

Bulk Agricultural Products: A rice exporter shipping 50,000 kilograms of rice in wooden pallets declares the net weight as 50,000 kilograms for customs purposes. However, the wooden pallet alone weighs 500 kilograms, and packaging adds another 300 kilograms, bringing the gross weight to 50,800 kilograms—what shipping companies charge for.

Key Takeaways

Understanding the distinction between net and gross weight is essential for anyone involved in manufacturing, logistics, e-commerce, or international trade. Net weight determines product value, pricing, and regulatory compliance in labeling and duties. Gross weight determines shipping costs, transportation safety compliance, and operational planning. Neither measurement is “more important”—they serve complementary functions, and accurate knowledge of both is required for cost-effective, compliant, and efficient supply chain operations.

The mathematical relationship (Gross Weight = Net Weight + Tare Weight) remains constant across all industries and transportation modes, providing a reliable framework for weight-based calculations. In an era where shipping costs represent a significant portion of product profitability and regulatory compliance carries substantial penalties, mastering these measurements is a competitive advantage for businesses of all sizes.